Re-wiring Local Governance: Aligning Regional and Local Decisions in a Changing Planning Landscape

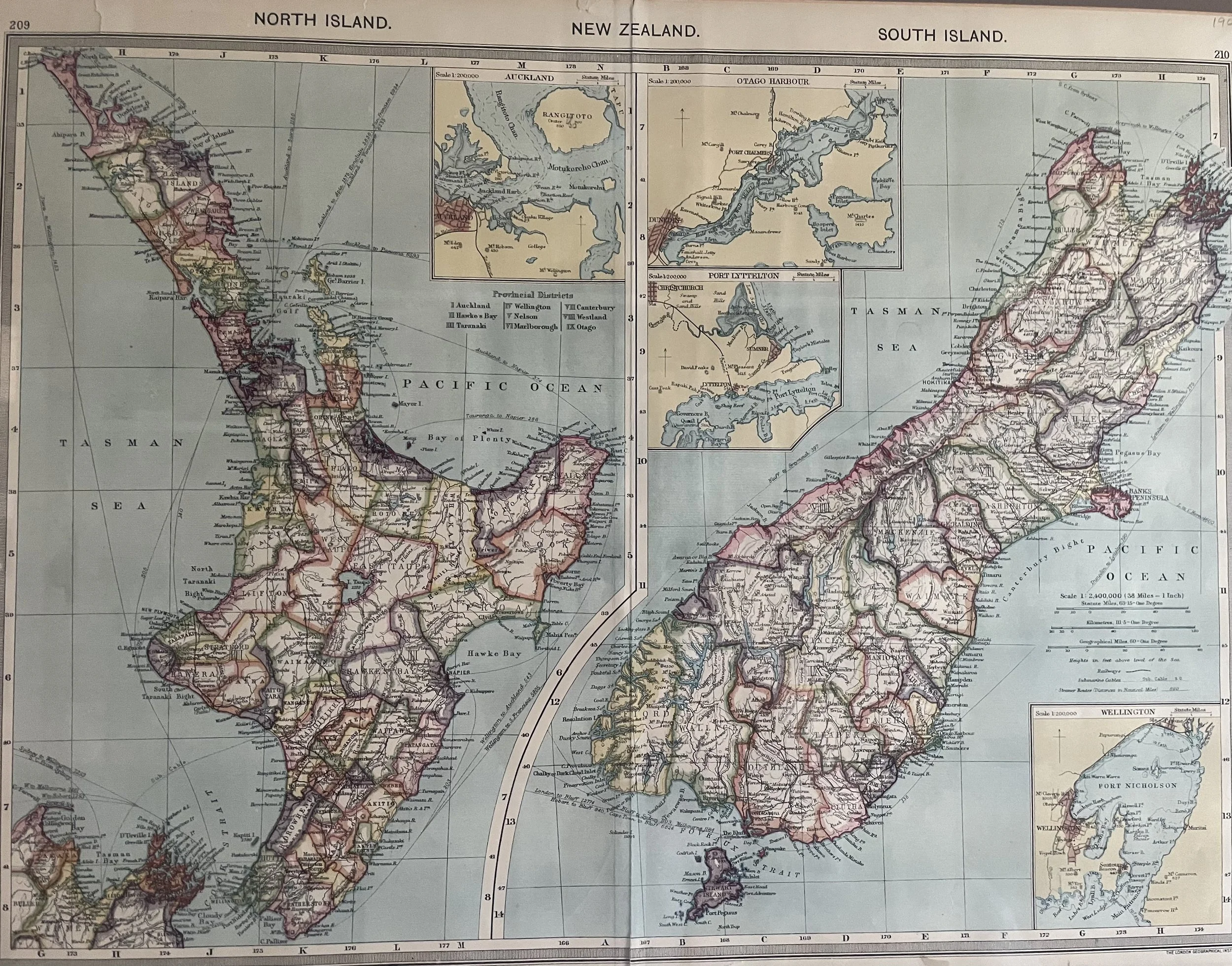

Historic map of New Zealand's provincial boundaries (1908). Regional boundaries have been reshaped several times since, including the major reforms of 1989.

Every so often the Government surprises those working across local and regional systems, and amid an already full reform landscape, the proposal to reshape regional governance announced on Tuesday arrived abruptly.

Most of us anticipated local government adjustments linked to the incoming resource management system, including fewer plans, clearer national direction, and a slimmer regional role. But the proposal to abolish elected regional councillors entirely and replace them with Combined Territories Boards (CTBs) was not widely signalled. It represents a significant shift in who makes regional decisions and how regional issues will be governed, should the proposal proceed.

Importantly, these changes are not yet Government policy. They form part of a draft proposal released on 26 November 2025 for public consultation, with submissions open until 20 February 2026 and final decisions yet to be made.

What the Draft Proposal Includes

Although CTBs have attracted the most attention, the draft proposal actually sets out three governance options for consultation.

The first is a Combined Territories Board made up of district and city mayors.

The second is the use of Crown Commissioners to undertake regional functions where a governance reset is required.

The third is a hybrid model that combines mayoral representatives with appointed commissioners.

All three options would replace elected regional councillors, but they differ in how regional leadership, expertise, and accountability would be configured. This article focuses specifically on the CTB option.

A closer connection between regional and district decision-making has real value

Planning practitioners know that regional and district issues are deeply interconnected. Growth pressures, infrastructure timing, freshwater limits, transport networks, natural hazards, and climate adaptation do not fall neatly within one tier of government.

In this sense, bringing district and city mayors into regional decision-making is logical. Mayors often have a clear sense of local pressures, including where housing demand is concentrated, which networks are under strain, and what communities expect from major investments in their areas.

Stronger integration between district and regional perspectives could help resolve long-standing disconnects between local land-use decisions and environmental constraints.

Historic data, however, indicates that integration in the form of unitary authorities may not lead to cost efficiencies. Recent operational and capital expenditure benchmarking by Rationale shows no clear cost-efficiency advantage for unitary authorities, suggesting that governance structure alone is unlikely to resolve the financial pressures many councils face.

But CTBs will require new and specialised capability, and quickly

While mayors bring essential local insight, the CTB model hands them responsibility for functions traditionally overseen by regional councils and specialist environmental teams. This includes catchment management, freshwater allocation, biodiversity protection, natural hazard risk management, and compliance and monitoring.

Under a CTB model, mayors will need more than a solid understanding of local issues. They will need:

a clear strategic vision for their district or city

the ability to negotiate and advocate for outcomes that balance community needs with environmental responsibilities

confidence working with complex science, statutory frameworks, and regulatory trade-offs

comfort with collective decision-making across a region and the ability to navigate compromise.

This shift could be particularly challenging for mayors with limited governance experience, or those elected on single-issue or highly localised platforms. CTBs demand a regional mindset and the ability to navigate significant environmental responsibilities that carry statutory obligations and, in many cases, Treaty settlement commitments.

For CTBs to succeed, members will require:

strong and consistent induction and ongoing training

dedicated environmental, scientific, economic, and policy expertise

shared regional data and monitoring systems

transparent and reliable decision-making protocols

well-defined partnership arrangements with iwi, particularly where Treaty settlements intersect with regional functions

leadership development to support negotiation, strategic thinking, and systems-level trade-offs.

Without this capability framework, variability across regions could emerge not by intention, but through uneven skill sets and support structures. The risk is that communities lose out in the long term if their mayors are not suitably prepared and equipped for strategic regional planning and the significant trade-offs it will require. Regions with stronger governance capacity may advance coherent, future-focused strategies, while others could struggle to keep pace, leading to unequal outcomes over time.

Representation on CTBs Needs Flexibility

Although the CTB model centres regional governance around mayors, this design choice raises a practical concern. In many districts and cities, the mayor may not be the elected member with the deepest experience in environmental management, spatial planning, transport, Treaty partnership, or infrastructure. Councils often have councillors with specialised portfolios or long-standing committee roles who may be better equipped for complex regional decision-making. Allowing each council to nominate one elected representative, whether the mayor or another councillor, could strengthen the capability and balance of the CTB. A more flexible representation model would recognise that effective regional governance depends not only on local mandate but on the right mix of skills, experience, and capacity around the table.

Regional reorganisation plans may reshape the system, but outcomes will vary by region

Every CTB (or Crown Commissioner, should one be appointed) will be required to prepare a regional reorganisation plan within two years of establishment. These plans must explore options such as:

shared services

new regional delivery entities

reallocating functions across councils

or merging councils into new unitary authorities.

As outlined in the draft proposal, each plan must be assessed against criteria relating to national priorities, service quality, affordability, local say, Treaty arrangements, leadership clarity, and implementability.

Because regions differ significantly in geography, demographics, infrastructure condition, and iwi relationships, these plans will not produce a single national model. Some regions may pursue structural consolidation. Others may favour closer collaboration while retaining existing boundaries.

If implemented, these plans will define the next decade of local government change.

The proposed Local Government Act changes are still at consultation stage

Given the scale of the proposals, it is important to emphasise that:

No amendments to the Local Government Act have yet been introduced to Parliament.

The CTB model is one option that Government is consulting on.

Alternative models such as Crown Commissioners or mixed CTBs are also on the table.

Regional reorganisation plans are a second step and would only be required if a region first adopts either a CTB or Commissioner model.

The draft proposal sets out a clear pathway: consultation, refinement, Ministerial decisions, and then legislation if Government chooses to proceed. At present we are firmly in the consultation phase, not the legislative one.

What we can say with confidence now

Although the proposals are at an early stage, several observations can already be made:

The need for strong, consistent environmental regulation will remain regardless of the governance model, and CTBs will need sufficient capability to meet statutory obligations in areas such as freshwater, biodiversity, and natural hazards.

Recent benchmarking of council operating and capital expenditure shows no clear cost-efficiency advantage for unitary authorities, suggesting that governance structure on its own is unlikely to resolve underlying financial pressures.

The changes would significantly shift regional political accountability, concentrating decision-making in a board of mayors rather than region-wide elected members.

Integration between district and regional priorities is likely to strengthen, particularly for growth, transport, and infrastructure.

Capability will be the critical success factor, given the varied governance experience and technical background of CTB members.

Regional reorganisation plans would strongly influence the long-term structure of local government, but outcomes would differ by region.

Final thought: A surprising shift, but with real potential if capability is prioritised

The scale of the announcement surprised many, but the opportunity it presents is substantial. With careful design, strong capability, and genuine partnership with iwi, CTBs could help align local priorities, regional responsibilities, and environmental management in a much more coherent way.

However, the proposals are still early and open for feedback. What happens next will depend on the quality and clarity of submissions, and on the Government’s final decisions once consultation closes. If adopted, these reforms would represent the most significant shift in regional governance since 1989.

Integration is the opportunity. Capability is the challenge. Consultation will determine the path ahead.